The simplest exercise with the biggest benefits

July 28, 2019

Looking at shoulder health from a wider perspective

August 15, 2019

It’s one of those topics isn’t it, the one greatly feared sporting injury is to pick up an ACL rupture which will put a full stop to your sporting endeavors as well as sideline you for 6-12 months and a lengthy rehabilitation. I’ve written this article to clear up a few unknown facts about the protocol but also to give you some information on what actually goes into rehabilitating one of these.

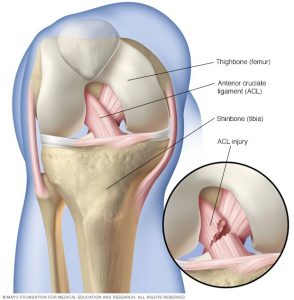

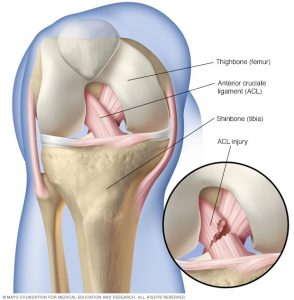

Firstly a little anatomy so you’re up to speed on what the ACL is and what it does.

It’s one of 4 main ligaments in the knee and connects your femur to your tibia. It’s function is to provide knee stability and resist excessive forward movement of the tibia.

ACL injuries typically come about for a number of reasons, these are broken down into intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic are the ones coming from your body and extrinsic being the environment you’re in when it happens.

Intrinsic factors could include your ankle and hip range of motion, co-ordination, fatigue and ability to control deceleration. Extrinsic factors could include being pushed, the grass/court you’re playing on and even your shoe type.

ACL injuries typically go like this, a person suddenly decelerates to quickly change direction and on the propulsion into that new direction they feel a sudden click, pop or the sensation of something giving away in their knee and they hit the deck holding their knee. Signs to identify if it’s your ACL that’s injured usually are high level pain and immediate gross swelling into the knee with a withdrawal from sport because you just can’t continue playing, it’s too unstable.

Another way to do it is to jump and land with your knee caving inwards medial to your ankle and hip and again same pop/click felt followed by an all expenses paid one-way trip to pain town.

It’s best to get your knee assessed as soon as possible because once the swelling gets so big the pain and swelling masks the special tests for the knee and muddies the clinical picture. What’s called a Lachman’s test is very reliable and sensitive in detecting an ACL rupture and a MRI can give clarity about any other intra-knee damage done i.e. cartilage damage, associated tibial fracture (Segond fracture on th tibia), meniscal tear or medial collateral ligament (MCL) sprain which usually happen with an ACL rupture.

Selection for surgery is dependent on a few factors:

- Age: the younger the athlete the more likely they’ll need an ACL so reconstruction can be indicated.

- Occupation: do they need an ACL for work

- Commitment: will the person see the rehab process the whole way through as poor compliance in the rehab process has been linked with re-rupture

- Sporting level: are they professional and do they need to be able to jump, land and pivot.

Treatment starts with prehabilitation. This is basically reducing the swelling, normalizing the range of motion and educating you on what to expect at the hospital coming up to the surgery, the rehabilitation road after the surgery and setting some realistic goals for the rehab between yourself and your physio.

Here’s a little information about what goes into the surgical process to help clear up any uncertainty about what goes into reconstruction an ACL.

Here’s a little information about what goes into the surgical process to help clear up any uncertainty about what goes into reconstruction an ACL.

An ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is done arthroscopically (keyhole), this means the surgeon will cut a number of small holes, usually 2-3, around your patella to attach the new ACL graft. This graft is taken from usually one of two places from the individual (an autograft). The first being the patellar ligament, called a bone-patellar-bone graft, from the front of your knee and the second is a hamstring graft taken from the back medial corner of your knee from the gracilis and semitendinosis muscles. In the old days surgeons used to use an allograft which was an ACL graft taken from a cadaver (a dead guy) but research has shown that success rates are better if the graft is taken from the subject themselves, better acceptance of the graft by the immune system and less likely chance of introducing infection etc.

The graft is anchored using screws or staples into the bottom of your femur and the top center of your tibia in what’s called the isometric point where the graft is under constant tension through knee range of motion. The arthroscopic portal scars will be closed and you’ll wake up from your anesthetic-induced beauty sleep.

For the first 2-4 weeks you’ll likely be on crutches in partial weight bearing moving towards full weight bearing and your knee protected in a hinged knee brace. You knee will be stiff, sore and achy after all the prodding around in the operating room but don’t worry all that stiffness and achyness will subside with time, good sleep and getting going on rehab firstly to restore range of motion (ROM) and clear the swelling.

First goal of the rehab process is to reduce the swelling, this can be done by icing the area, using a compression sleeve like tubigrip and look LOTS of range of motion exercises to help pump that swelling out of the knee capsule. Once the little portal scars are closed we start releasing them as the sensitized scar tissue can be a huge factor is delaying getting you’re full range back as well as contributing to ongoing pain so key to nip those early when they’re closed.

Next stop is soft tissue treatment to reduce any pain and shortening as a result of the surgery and then start stretching to regain normal range of motion in your ankles, knees and hips. Once you’ve full range of motion we start re-training your squatting, lunging and dead lifting movement patterns, which may have been altered by the surgery and acute stage of recovery, whilst working on balance training.

Once normal, full range of motion has been established in the local joints and movements we start loading those movements to develop strength an control in the squat, lunge, step and dead lifting patterns. Here we want to build your strength up to pre-injury levels or the goal set in the prehab stage.

Once we’ve hit full strength and neuromuscular control we drop down the repetition range to 2-3 to start developing power as we move into the ballistics/plyometrics phase which includes move a moderate weight quickly and with intensity. Here we can introduce hopping, bounding and jumping into the program further solidifying control and trust in your knee.

Once we’ve fully regained flexibility/mobility, co-ordination (motor patterning), balance, strength and power we start introducing cardiovascular endurance and building stamina on you’re operated leg. Up until now cardiovascular endurance should have been maintained by doing upper limb exercises like the upper body ergo meter and walking for the lower body but now we start introducing running to build fitness.

Once running is strong we introduce speed training then agility work. Lastly sport specific drills to prep you for you’re return to sport/performance.

Decision to return to sport is made on a number of calls e.g. pain-free, ROM, strength, knee stability and control, power production, type of sport returning to, therapist and coach opinion but arguably the most important is the patient’s confidence in their knee and their confidence in returning to sport. The return to sport is a graduated one firstly going to training and performing at 50% of the session at 50%, then next session at 75% as long as there are no issues and 3rd is full training session. On reintroduction to competitive play after 100% training the player should only play the 20 mins and build up from here to full match play. The entire rehab process usually takes between 6-12 months with 9 being the median.

I hope this was useful for you, is you are interested in ACL rehabilitation I’m a specialist and please feel free to contact us at DISC and we can get you on the road to recovery.

Redmond C.

[ad_2]

Source link

1 Comment

Awesome post.